The following is a collaborative post with Ed Lajoie, a research specialist and assistant project manager for the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery. There, he investigates landmines and the usage of minefield markings in post-conflict areas. In this post, we discuss a few principles of communication and design in the context of communicating danger in minefield markings.

As an assistant project manager at the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery, much of my job consists of helping those affected by landmines and unexploded ordnance (UXO). Each of my team members must take into account the culture and historical precedents of where ever these ordnances will take place, countries such as Tajikistan, Jordan and Croatia. However a growing interest of mine has been to investigate how various cultures use design or “markings” to communicate danger in these areas.

Early on in my fieldwork, I learned an important lesson in communication: the meaning of communication is the response you elicit, not what you intended. The purpose of communication is to make a change in the other person. Hence we must not get too married to our preconceived notions about the “correct” communication.

In most cases, an area contaminated with land mines or explosive remnants of war does not stand out from the surrounding land. So it is up to humans to communicate the location(s) of a danger zone. As in, civilians bear the responsibility of warning each other of the hazards when crossing the invisible line.

A trained observer may detect certain signs: animal bones laying in the open air, changes in vegetation patterns, slight deformation of the terrain from cratering, but for the most part these deadly fields do not advertise their presence.

We, as communicators are responsible for ensuring the appropriate communication is understood, not just delivered. To be effective, we as (designers, or businesses) communicators must modify our communication until the appropriate message is acted upon. Minefields and UXO areas are extreme examples of this scenario, as lives may be lost.

Minefields and unexploded ordnance contamination are found worldwide, so it’s important to relay messages signifying danger that are both universal and flexible enough to be adaptable to different cultural environments.

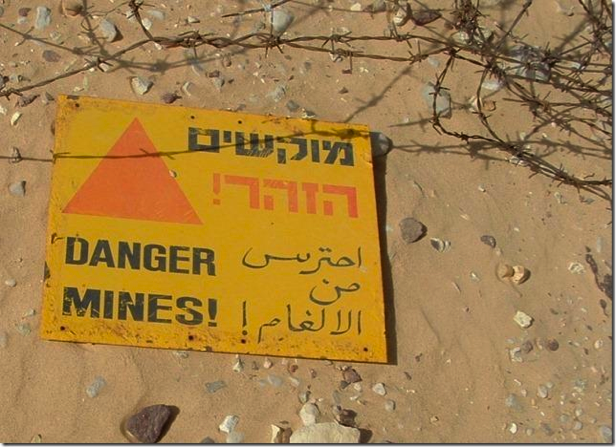

Here’s an example of a minefield marking sign in Tajikistan:

Pretty clear, right? I would hope so, considering the man appears to be having his leg blown off.

The Goal of Design

Design is primarily a visual goal-oriented communication. The goal is always primary. The goal will determine what decisions made related to that design and communication. In other words, a designer’s aesthetic decisions are made in the service of his or her goals for the communication.

When it comes to minefield markings, the goal is to communicate entry into a danger zone, regardless of literacy levels or fluency in local or international languages. Effective communication can save lives.

The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) as part of its International Mine Action Standards (IMAS) developed IMAS 08.40–a design standard in order to specify “the minimum requirements for the marking of mine and ERW hazards (including unexploded sub-munitions) and hazardous areas.” In developing this standard, UNMAS drew on three pieces of international humanitarian law: The Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty, Amended Protocols II and V to the UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW); and the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM).

IMAS 08.40 contains specifications for everything from boundary fence heights to the materials from which signage should be constructed (they should be locally sourced and not have value as a construction material lest they be appropriated for local use.) Most interesting, however, is the IMAS’ recommendation on symbols and colors used in the signage design. It is these specific elements that are what is directly responsible for conveying the message of danger to whoever is approaching the contaminated area.

Annex B of IMAS 08.40 states “The sign should have a red or orange background with a white symbol for danger. The universal symbol for danger is the skull and crossbones, however the NMAA (National Mine Action Authority) may specify another symbol if the skull and crossbones is not appropriate. The words “danger mines” (or danger UXO depending on the predominant hazard) should appear on the sign in the local language(s).”

Another example:

Notice any similarities? Not only is the messaging clear to the average civilian, but the overall design (image and color specifications) of the sign meets international requirements for communicating danger.

In design and art, color theory guides designers in mixing colors and creating effective color combinations, sometimes for the purpose of evoking specific emotions or reactions. The meanings of various colors are subjective and culturally dependent. In fact, depending on the language spoken, a language may or may not have a word for a secondary or tertiary color. As a designer or professional communicator, it can be important to make distinctions between things that are universal, cultural, or idiosyncratic to the individual. This can help us ensure our our own personal or cultural biases are not generalized inappropriately.

Red, yellow, and orange colors– although a language may not have a word for each color– are perceived by non-colorblind individuals. Furthermore, they are universally “hot” colors, hence, they are nearly always used to communicate danger on signage using international standards.

Finally, what about areas without signs? Are there alternative ways to communicate danger?

Yes. In many areas where locals are unaware or unable to utilize IMAS compliant marking systems, field expedient measures are used.

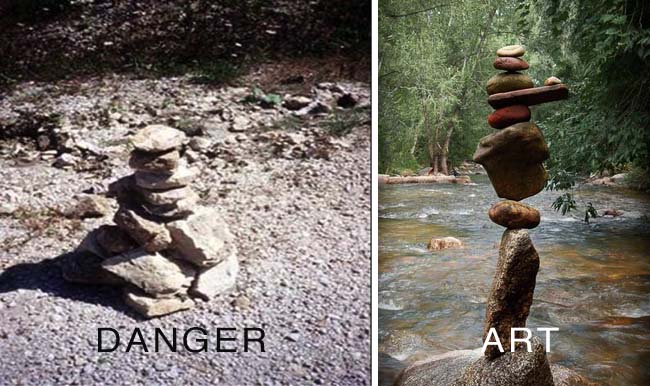

Take a look at this creative minefield marking in Tajikistan:

You can be sure the person who made this signal is communicating to his or her social group. In this case, it’s an improvised system to communicate danger. It’s not a universal signal for a minefield, but it is effective in this culture or geographical proximity, and it does indicate a human was attempting to communicate something. If a foreigner is around, however, then they’re in trouble.

There are local ways of signaling the danger of ERW contaminated land or mine, which might include knotted grass and stones piled into a pyramid shape. The IMAS designates these ways of marking as improvised marking systems and recommends that they replaced with something more permanent as soon as possible.

It is important though that these methods be recognized as another equally important way of communicating the hazard of these areas and respected in the same way as internationally standardized signage. Yet, markings such as the one on the left could be easily misconstrued for something else.

Some improvised markings are a bit more effective if they relate to something more universal, for instance, if they bear the cross sign similar to the one below:

What does minefield markings teach us about design and communication?

Minefield marking incorporates the same principles in design (nonverbal communication). Effective minefield markings attempt communication that is universal and flexible. The ability to communicate something as universal as danger requires a sharing of contextual and social conventions. When this is not available, we must be flexible enough to communicate to as many people as we are able.

My coworkers must take into account the culture and historical precedents of wherever it will take place. And in turn, it would require more flexibility, as it must be broadly recognizable so as to be understood by a wide range of actors and capable of being replicated in different environments.

By Ed Lajoie,

Assistant Project Manager & Research Specialist, Center for International Stabilization and Recovery

Special thanks to Andy Smith, Sean Sutton, Mustafa El Kabti, and Daler Mirzoaliev for their insight and expertise. For further information about the International Mine Action Standards check out this website.

To learn more about the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery go to: http://cisr.jmu.edu/

This article first appeared at https://studioissa.com/warning-signs-how-landmines-can-teach-us-about-project-design-and-communication/